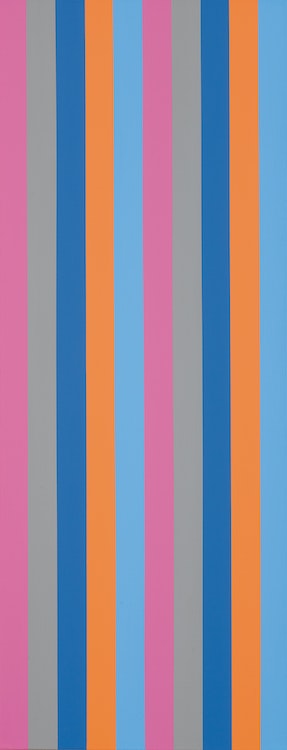

A founding member of the second group of “Les Plasticiens” in Montréal in 1955 and constantly innovative throughout his long career as a painter, poet, and university teacher, Guido Molinari was a prominent spokesperson for abstract art from the 1950s until the 2000s. There is no abstract painter in Canada who delved deeper into the profundities of the genre than Guido Molinari, which suggests why “Bi-sériel rose” is as vibrant and immediate now as when it was painted in the late 60s.

Molinari’s rigorously organized canvases require our close, even literal, attention. Both geometrically regular and chromatically complex, they work optically, corporeally, and intellectually. “Bi-sériel” rose clearly announces its key colour and organizing principle. We see two series of five colour bands; from left to right, rose, grey, darker blue, orange, and lighter blue. Because his individual colours work together (the orange and darker blue as complementary colours, for example), however, in addition to isolated stripes, they stand out as blocks in what remains a repeated sequence with variations. Individual colour columns repeat, but so do pairs of colours. The painting does not allow us to rest optically, nor does it have a stable centre (impossible with ten colour bars, unless one pairs two in the middle, as Molinari does here, leaving four symmetrical flanking columns on the left and right). Instead, our eyes and our bodies (because the painting is vertical and at a human viewer’s scale) are moved by the colour bands. We take part in a chromatic and intellectual game whose conventions are established by the painting. The game is complex but not infinite: the sequence is also clearly bounded by the fame, guaranteeing that the left edge (rose) differs from that at the right (light blue).

While “Bi-sériel rose” is primarily a painting to be taken on its own optical terms, Molinari‒akin to many abstract artists‒responded to the ambient world and encouraged his canvases to reverberate well beyond the frame. The sériels from this period, for example, were inspired by and closely cognate with his interests in the modern classical music of Schönberg and Webern.

We extend our thanks to Mark A. Cheetham, a freelance writer and curator and a professor of art history at the University of Toronto for contributing the preceding essay. He is author of “Abstract Art Against Autonomy: Infection, Resistance, and Cure since the ‘60s” (Cambridge University Press).